This blog post is the preface for Luca Belli and Nicolo Zingales (Forthcoming). Platform Regulations. Official Outcome of the UN IGF Dynamic Coalition on Platform Responsibility, to be presented at the Internet Governance Forum 2018.

2017 presented increasingly difficult challenges for digital platforms such as social media and search engines. Consider the most high profile among them, Facebook. The year of challenges began in 2016 just as Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, after which public outrage – among Democrats and “Never Trump” Republicans at least – focused on the spread of “fake news” on platforms like Facebook. A New York Magazine headline proclaimed, “Donald Trump Won Because of Facebook,” while The New York Times, in an editorial entitled, “Facebook and the Digital Virus Called Fake News,” asserted that CEO Mark Zuckerberg “let liars and con artists hijack his platform.” In fact, 2017 may well be remembered as the year when platform harms, and the demands to address them, became widely understood in the mainstream as a leading problem of public policy in digital space.

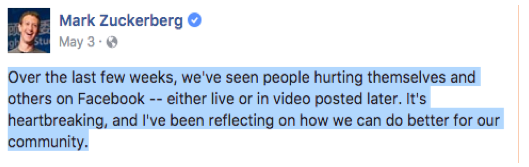

The challenges did not end with demands of platform responsibility for disinformation and propaganda. In May, Zuckerberg, evidently under pressure to respond to a range of perceived ills on his platform, posted a note that began as follows:

The content of the note could not be a surprise to anyone who has followed the news in recent years: an admission that certain kinds of harm may occur, or be seen to occur, on Facebook, particularly through video. Zuckerberg mentions three specific harms: hate speech, child exploitation, and suicide. He could have gone further. By 3 May 2017, the list of “harms” that he and others might have proposed here could have been extensive and gone well beyond video posts: the aforementioned “fake news” or “junk news”; promotion of terrorism or ‘extremism’; misogyny and gender-based harassment and bullying; hate speech in the form of inter alia racism, Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, homophobia; religious discrimination; reputational damage related to such doctrines as the right to be forgotten; and so on. And while Facebook surely is not alone in facing criticism – Twitter, Google/YouTube, Reddit, Snapchat and many others are in the zone, too – it is easily the largest social media forum and attracts the most attention.

Still, that opening paragraph deserves unpacking, especially its last eight words, which show Zuckerberg to be asking himself, ‘How can we do better for our community?’ Almost every word does some work here. How: is there a process available to address the perceived harms? We: is this a problem that deserves our corporate attention? Better: is there a standard of protection, whether of rights or physical and mental well-being, which the company seeks to achieve? For: Is content regulation something the company does “for” its users, top down, or something that it identifies in concert with them? Community: is it possible to talk about all users of a particular platform as a single community? What does the word imply about the nature of governance within it?

Even in the absence of such a Talmudic evaluation of eight words, it is impossible to read the post without concluding that Facebook is looking for ways to regulate its own space (and it and the other platforms are under immense pressure to do so). There is, for instance, no suggestion of outsourcing that regulation to external actors. It is an effort to look within for answers to fundamental questions of content regulation.

Not all actors in digital space see it the same way – or at least express their concerns in this way. Matthew Prince, the CEO of Cloudflare, a major content delivery network, faced what may seem to some to be an easy question: whether to remove Nazis from a platform. In the wake of the white supremacist marches and attacks in Charlottesville, Virginia, Prince faced pressure to end Cloudflare’s relationship with The Daily Stormer, a Nazi website and Cloudflare client. As he put it to his employees, “I woke up this morning in a bad mood and decided to kick them off the Internet.” But that was not all. He posted an essay in which he struggled with this question: why, he asked, should I police Nazis and others online? Is that not government’s function and authority? His point cannot be ignored: “Without a clear framework as a guide for content regulation, a small number of companies will largely determine what can and cannot be online.”

This volume seeks to capture and offer thoughtful solutions for the conundrums faced by governments, corporate actors and all individuals who take advantage of – or are taken advantage of within – the vast forums of the digital age. They aim to capture the global debate over the regulation of content online and the appropriate definition of and responses to harms that may or may not be cognizable under national or international law. In a perfect world, this debate, and its resolution, would have been addressed years ago, in times of relative peace, when content-neutral norms might have been developed without the pressure of contemporary crises. Today, however, the conversation takes place in the shadow of grave violations of the freedom of opinion and expression and a panoply of other rights – privacy, association and assembly, religious belief and conscience, public participation. We all find it difficult to separate out the current crises and alleged threats from the need to ensure that space remains open and secure for the sharing and imparting of information and ideas.

In reading through this volume, two things are likely to become clear. First, there is a set of difficult normative questions at the heart of the platform regulation debate, centered on this: What standards should apply in digital space? Or more precisely, what standards should the platforms themselves apply? Are the relevant standards “community” ones, rooted in a sense of what’s appropriate for that particular platform? Should they be based on norms of contract law, such that individuals who join the platform agree to a set of restrictions? Should those restrictions, spelled out in terms of service (ToS), be tied to norms of human rights law? Should they vary (as they often do in practice) from jurisdiction to jurisdiction? In accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, what steps should companies be taking to ensure they respect rights and remedy violations?

A second set of questions is based on process. Some of them will be answered differently depending on how the standards question is answered. For instance, if we agree that the standards should be fully defined by the platforms themselves, procedural norms will likely not touch upon matters of public policy or public law. However, if the standards are tied to public law, or if government imposes standards upon the platforms, who should be adjudicating whether particular expression fails the standards? Should governments have a role, or should courts, in cases involving the assessment of penalties for online expression? Or should the platforms make those determinations, essentially evaluating the legitimacy of content based on public standards?

This is a volume for all stakeholders, reinforcing the critical – perhaps foundational – point that content regulation is a matter of public policy. As such, the debate is not one for governments and companies to hash out behind closed doors but to ensure the participation of individuals (users, consumers, the general public) and non-governmental actors. It is one that will benefit from the consideration of the role of human rights law, particularly since online platforms have indeed become the grand public forums of the digital age. It is finally one that must aim toward the protection of those rights that all too many governments seem eager to undermine.