Since the adoption of the mandate in 1993, successive rapporteurs have addressed core issues involved in advancing the freedom of expression. They have developed methodologies to, in the words of Council Resolution 7/36, “seek, receive and respond to credible and reliable information” alleging violations of the right to freedom of expression, addressing to governments hundreds of the Allegation Letters and Urgent Appeals that are at the center of the mandate’s day-to-day work. They have conducted dozens of country visits in order to explore compliance with the norms of freedom of expression at national and local levels and to benefit from the insights of governments and non-governmental actors. They have collaborated with governments and international organizations, and they have drawn upon the remarkable commitment of civil society organizations, at national and international levels, to advance freedom of expression norms. They advocate for the protection of defenders worldwide while helping shape our understanding of the application of norms in situations of tremendous flux, particularly in areas of the internet and high technology.

It is appropriate that I begin my own tenure by acknowledging the foundation laid by the three special rapporteurs who have advanced freedom of expression since the mandate was established in 1993.

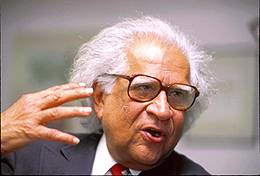

The first mandate-holder, Mr. Abid Hussain of India, passed away in 2012. Mr. Hussain served the people of India for decades in industry, trade, education, public service, and diplomacy. Reaching far beyond India, his contribution as special rapporteur set the tone for his successors when he noted in his first report:

“The conclusions and recommendations will be action-oriented. The Special Rapporteur’s experiences in practice will form their basis. Their object will be the better protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and their purpose the elimination of violations of this right.”

From 1993 to 2002, Mr. Hussain addressed critical issues. On the nature and scope of limitations to the right, he concluded that “any interference, and especially restriction or limitation [on the exercise of freedom of expression], should be interpreted narrowly in case of doubt.” In 1998, he expressed the belief that “the right to access to information held by the Government must be the rule rather than the exception,” and his was an early voice advocating the free flow of information on the then-nascent internet. In his 1999 report to the Commission, he called for accountability for attacks on journalists, expressed concern about the misuse of national security laws to undermine expression, and bemoaned the impact of criminal libel laws, which create “a climate of fear in which writers, editors and publishers become increasingly reluctant to report and publish on matters of great public interest not only because of the large awards granted in these cases but also because of the often ruinous costs of defending such actions.” With the critical assistance of Article 19, the Center for Law and Democracy, and other organizations devoted to freedom of expression, Mr. Hussain developed critical working relationships with colleagues in the Inter-American system, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and, later, the African Commission, adopting annual statements on key freedom of expression issues.

In 2002, Mr. Ambeyi Ligabo of Kenya succeeded Mr. Hussain as special rapporteur. Mr. Ligabo addressed such topics as access to information and the scourge of HIV/AIDS, the impact of counter-terrorism measures on freedom of information, the protection and security of journalists and media professionals, the chilling effects of defamation laws, and the connection of freedom of expression to the realization of other human rights. Mr. Ligabo made a major contribution to the promotion and protection of freedom of expression in many areas, in part because of his willingness to challenge existing or emerging trends in critical areas. For instance, in his 2005 Report to the Commission, he foresaw the potential of a deepening digital divide between the affluent and the poor, and he urged non-state actors, the United Nations, States and civil society “to cooperate closely in order to make sure that human rights will be a fundamental and unavoidable component of the future of Internet governance.” His final report, in 2008, reminded governments of the importance of adopting national legislation to ensure the exercise of freedom of expression and recommended that States adopt “media independence” as a major priority, including “website contributors and bloggers” within the class of protected persons.

Mr. Frank La Rue of Guatemala succeeded Mr. Ligabo in 2008. During the six years of his mandate, Mr. La Rue built upon the findings and recommendations of his predecessors, including in such areas as efforts to expand access to information in situations of extreme poverty, the protection of journalists and specified vulnerable groups, and abuses of the freedom of expression in times of elections and transition. In his 2012 Report to this body, Mr. La Rue paid particular attention to the challenge of hate speech and incitement to hatred, violence, and discrimination, insisting upon the principle that limitations on the right should be limited to extreme cases and urging States that have them to repeal any laws against blasphemy. Mr. La Rue also continued the tradition launched by Mr. Hussain of annual statements with the regional freedom of expression rapporteurs; their 2010 statement of ten key challenges should be seen as a reflection of a broad commitment to address the major barriers to free expression today.

Mr. La Rue also saw that a central objective of the mandate would have to involve confronting threats against freedom of expression on line. Though many of his reports addressed expression on-line, Mr. La Rue’s reports in 2011 (to the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council) and 2013 focused directly on trends implicated by the relatively new centrality of on-line communication to freedom of expression. Among the trends he noted were harassment and intimidation of bloggers and journalists by the hacking of their accounts, arbitrary arrests, online monitoring, and blocking of websites; the blocking of website content through filtering or the take-down of websites altogether, including at key political moments such as elections or during protest; the criminalization of online expression, such as defamation, blasphemy, lèse majesté, public official insult, and government criticism; the imposition of liability on intermediaries for the actions of third party users; the use of cyber-attacks to crash websites of political opposition or protesters; and the weakness of infrastructure in the developing world, undermining access to the internet and digital literacy. Mr. La Rue noted that human rights law permits restricting online content when involving child pornography, direct and public incitement to commit genocide, advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence, or incitement to terrorism. He also emphasized that the best strategy to counter offensive or intolerant content is the availability of additional avenues for speech to counter ugly expression. Mr. La Rue’s 2013 report was among the first to highlight the impact of government electronic surveillance on freedom of expression, criticizing the ability of governments to monitor and intercept private communications and the practice of mass surveillance in the absence of judicial oversight.